This month's Round Robin Blog asks: What do you define in your writing about your characters and what do you leave to the reader’s intuition? Is there anything you never tell about a character?

XX

XX

The answer to this question depends on what we mean by define? For me, I’m going to assume that define means telling the reader what a character is like. Not necessarily what they look like but what kind of person they are. So, using this definition of define, I try NOT to define my characters but rather to show the reader what they are like.

XX

For the obvious, rather than tell the reader that Mac had a soft spot for dogs, I show him rescuing an abandoned puppy. I follow that up with how he treated it in the days that followed, in his efforts to find the puppy’s owner, and his growing dismay to find he didn’t want to find the owner. Now the reader knows how Mac feels about dogs in general and this one in particular without me specifically defining his feelings toward the dog.

For the obvious, rather than tell the reader that Mac had a soft spot for dogs, I show him rescuing an abandoned puppy. I follow that up with how he treated it in the days that followed, in his efforts to find the puppy’s owner, and his growing dismay to find he didn’t want to find the owner. Now the reader knows how Mac feels about dogs in general and this one in particular without me specifically defining his feelings toward the dog.

XX

For the less obvious, things like loyalty, chivalry, honesty, kindness, or their opposites: disloyalty, deceiving, mistreating  women or ignoring people in need, I again try to show the reader what’s in my character’s hearts by their actions. If I have my character brush angrily past an old woman fumbling with her parcels because he is in a hurry or perhaps doesn’t even notice her, then the reader gets a pretty good idea of this person’s character without me saying he was callous or rude. Just as I could have a well-dressed business woman in a hurry

women or ignoring people in need, I again try to show the reader what’s in my character’s hearts by their actions. If I have my character brush angrily past an old woman fumbling with her parcels because he is in a hurry or perhaps doesn’t even notice her, then the reader gets a pretty good idea of this person’s character without me saying he was callous or rude. Just as I could have a well-dressed business woman in a hurry  for an important interview stop to help a distressed child who is obviously lost. Knowing it will mean missing the interview but stopping anyway. Now the reader has a good grasp on the type of person this woman is. Maybe she’s a mother and could relate to that child’s distress, but perhaps she’s not which makes her actions doubly revealing. The same goes for four-legged characters. One might prance eagerly, tail wagging furiously, or cower uncertainly or snarl menacingly. All show the reader what kind of dog this is, at least in this situation.

for an important interview stop to help a distressed child who is obviously lost. Knowing it will mean missing the interview but stopping anyway. Now the reader has a good grasp on the type of person this woman is. Maybe she’s a mother and could relate to that child’s distress, but perhaps she’s not which makes her actions doubly revealing. The same goes for four-legged characters. One might prance eagerly, tail wagging furiously, or cower uncertainly or snarl menacingly. All show the reader what kind of dog this is, at least in this situation.

XX

It’s a case of show rather than tell, but obviously the reader does need to know this character so they will understand why the character makes the choices they make. You might have a character which a history of abuse and it’s important for your reader to know this so they will understand why the character avoids certain people and situations. Or perhaps a character grew up dirt poor which explains

It’s a case of show rather than tell, but obviously the reader does need to know this character so they will understand why the character makes the choices they make. You might have a character which a history of abuse and it’s important for your reader to know this so they will understand why the character avoids certain people and situations. Or perhaps a character grew up dirt poor which explains  his or her pinching every penny until it squeals, or having finally hit the big time doing everything possible to erase their origins – like introducing friends to their parents or taking a college friend home for the weekend. Knowing where a character comes from not only helps the reader to understand choices made, but also to feel empathy for the character, or a sense of satisfaction or triumph for a success that might have been easy for someone else but was monumental for your character.

his or her pinching every penny until it squeals, or having finally hit the big time doing everything possible to erase their origins – like introducing friends to their parents or taking a college friend home for the weekend. Knowing where a character comes from not only helps the reader to understand choices made, but also to feel empathy for the character, or a sense of satisfaction or triumph for a success that might have been easy for someone else but was monumental for your character.

XX

Then there are the quirks a character might have. How much better is it to show the character carefully organizing their catch-all drawer, or hurrying around behind a roommate rearranging everything the roommate tossed haphazardly as they went through the apartment, than to flat out define this character as OCD? Or the character who bites their fingernails whenever they are stressed, or cowers when lightning zaps across the sky? A good author does not need to define those quirks – just show the reader and let the reader figure it out.

Then there are the quirks a character might have. How much better is it to show the character carefully organizing their catch-all drawer, or hurrying around behind a roommate rearranging everything the roommate tossed haphazardly as they went through the apartment, than to flat out define this character as OCD? Or the character who bites their fingernails whenever they are stressed, or cowers when lightning zaps across the sky? A good author does not need to define those quirks – just show the reader and let the reader figure it out.

XX

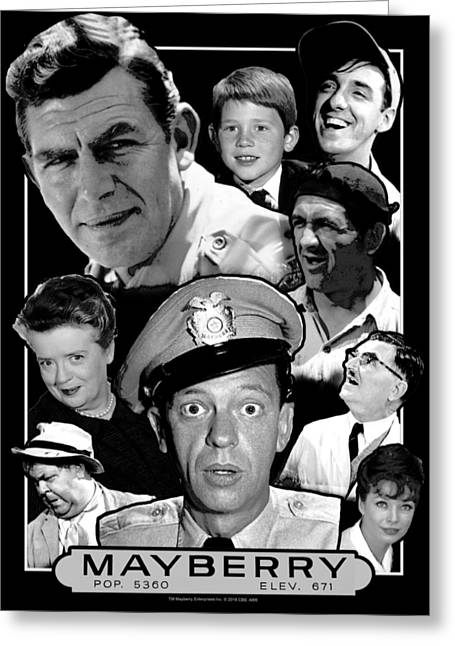

But showing a character’s personality without telling, also lets the reader develop their own relationship with that character rather than the author telling the reader how they should feel about them. In Mayberry RFD, no one tells the viewer that everyone loves Aunt Bea because she is kind, gentle, loving, thoughtful, the viewer gets to see Aunt Bea in action, supporting Andy, helping to rear Opie, interacting with townsfolk. We didn’t have to be told what kind of officer Barney Fife is, or that Otis has a problem with alcohol, we SEE them acting these characters out. That’s how I prefer to present my characters in my books. Not defining who they are, or what they are like in my own words but presenting them in a way the reader can see for themselves and form their own relationships with the characters.

But showing a character’s personality without telling, also lets the reader develop their own relationship with that character rather than the author telling the reader how they should feel about them. In Mayberry RFD, no one tells the viewer that everyone loves Aunt Bea because she is kind, gentle, loving, thoughtful, the viewer gets to see Aunt Bea in action, supporting Andy, helping to rear Opie, interacting with townsfolk. We didn’t have to be told what kind of officer Barney Fife is, or that Otis has a problem with alcohol, we SEE them acting these characters out. That’s how I prefer to present my characters in my books. Not defining who they are, or what they are like in my own words but presenting them in a way the reader can see for themselves and form their own relationships with the characters.

XX

So, my answer to the second question is I try to leave it all to the intuition of the reader. I want the reader to care about my characters because of how I’ve presented them, not because I have to tell them they need to care. I hope there is nothing about my characters I have failed to reveal, however. But that’s just me. Hop on over and see how my fellow monthly Round Robin Blog Hoppers approach the subject.

Connie Vines

Connie Vines

Dr. Bob:

A.J. Maguire

Robin Courtright

Helena Fairfax