Our June Round Robin Blog is digging into - How authors recognize and overcome plot problems or failures?

Our June Round Robin Blog is digging into - How authors recognize and overcome plot problems or failures?

XX

The first thing that occurs to me is that the answer to this question might be very different for Plotters vs Pantsers. So, since I’m a pantser, I’ll answer from my point of view and let the plotters in our group share their methods.

XX

Since the bulk of my books begin with a germ of an idea that I nurture with detailed character dossiers and a well-considered Goal/Motivation/Conflict chart for each, my writing is basically an adventure that I am on as much as my readers. I have no idea what’s going to happen next. With one main exception – I always know how the story will end. In fact, I’ve often written the final scene or chapter before I start the book because I can see it so clearly in my head. But once I’ve got my characters who I know as well as I know myself, I plop them into the inciting incident and let them run with the ball, so to speak.

Since the bulk of my books begin with a germ of an idea that I nurture with detailed character dossiers and a well-considered Goal/Motivation/Conflict chart for each, my writing is basically an adventure that I am on as much as my readers. I have no idea what’s going to happen next. With one main exception – I always know how the story will end. In fact, I’ve often written the final scene or chapter before I start the book because I can see it so clearly in my head. But once I’ve got my characters who I know as well as I know myself, I plop them into the inciting incident and let them run with the ball, so to speak.

XX

The first inkling I might have that there is a plot problem or failure is that my characters seem to have wandered into a blind alley and are left with nowhere to go. Clearly, they’re in enemy territory and need a road map to get themselves out of trouble. As one of my brainstorming buddies calls it, they went down a rabbit hole. Now I have to stop and ask myself why they chose that alley? Why did I write that scene? Who is this new character that walked on stage and redirected the action? I consider all the options, jotting down thoughts as they come to me. Sometimes I might even write whole scenes that seem to be out of place/sync which I end up filing in a “Bits and Pieces” file I have for all my books where I save clips, thoughts, scenes and parts of scenes I might include somewhere else.

The first inkling I might have that there is a plot problem or failure is that my characters seem to have wandered into a blind alley and are left with nowhere to go. Clearly, they’re in enemy territory and need a road map to get themselves out of trouble. As one of my brainstorming buddies calls it, they went down a rabbit hole. Now I have to stop and ask myself why they chose that alley? Why did I write that scene? Who is this new character that walked on stage and redirected the action? I consider all the options, jotting down thoughts as they come to me. Sometimes I might even write whole scenes that seem to be out of place/sync which I end up filing in a “Bits and Pieces” file I have for all my books where I save clips, thoughts, scenes and parts of scenes I might include somewhere else.

XX

I’m one of a small group of authors that meet regularly and we call ourselves the Sandy Scribblers (a nod to all the gorgeous beaches in our town.) Our meetings cover all aspects of the writing life, but often, I get to present my plot dilemmas when they leave me floundering, and it’s the whole issue of seeing the forest for the trees. One or another of my group immediately latches onto the very heart of where I went wrong. Then they all chime in with ideas on fixing it, or eliminating the out of place scene. Presenting my confused characters with a road map or sending in the Marines to rescue them.

I’m one of a small group of authors that meet regularly and we call ourselves the Sandy Scribblers (a nod to all the gorgeous beaches in our town.) Our meetings cover all aspects of the writing life, but often, I get to present my plot dilemmas when they leave me floundering, and it’s the whole issue of seeing the forest for the trees. One or another of my group immediately latches onto the very heart of where I went wrong. Then they all chime in with ideas on fixing it, or eliminating the out of place scene. Presenting my confused characters with a road map or sending in the Marines to rescue them.

XX

Another huge and glaring proof that I’ve got a plot problem is that dreaded “Sagging Middle” that all writers hate. This is likely the same for plotters, as well. We started out with a bang and ran 80 yards for a touchdown, rebuffed the opposing team’s efforts to catch up and had a sterling second quarter. Then abruptly things fall apart. A key player is sidelined with an injury, the defense is MIA and the quarterback has been sacked. Some authors excel at getting out of these tight spots – call them the Tom Bradys of the writing world. If you’ve ever seen that man play, you’ll know he can seem totally overwhelmed, the

Another huge and glaring proof that I’ve got a plot problem is that dreaded “Sagging Middle” that all writers hate. This is likely the same for plotters, as well. We started out with a bang and ran 80 yards for a touchdown, rebuffed the opposing team’s efforts to catch up and had a sterling second quarter. Then abruptly things fall apart. A key player is sidelined with an injury, the defense is MIA and the quarterback has been sacked. Some authors excel at getting out of these tight spots – call them the Tom Bradys of the writing world. If you’ve ever seen that man play, you’ll know he can seem totally overwhelmed, the  score heavily lopsided in his opponent’s favor, unable to connect with his best receivers, and is scrambling just to keep from losing the ball. Yet somehow, he comes back in the fourth quarter and pulls a rabbit out of a hat.

score heavily lopsided in his opponent’s favor, unable to connect with his best receivers, and is scrambling just to keep from losing the ball. Yet somehow, he comes back in the fourth quarter and pulls a rabbit out of a hat.

XX

But Brady’s comeback didn’t happen by chance. There was some serious soul searching going on during that last break in the locker room that breathed new life into his team. This is what an author needs to do. Have a heart to heart with each of the major characters. Ask them how they feel about where they are, how they got there, what they plan to do about it. Maybe even threaten them to pull themselves together and get back on track.

XX

My brother used to amuse our family with a completely unrehearsed discussion between a Scotsman and an Englishman, complete with accents that had us in stitches. His repartee hopped back and forth between the two and that verbal jousting was as realistic as if two entirely different people were having the discussion. This is often a tool a writer equally gifted might use all by themselves. But another way to get this pep talk under way is to bounce it around with a couple other writers. Every mind works differently so looking at your cul de sac with a trusted group of writers can produce remarkable breakthroughs.

My brother used to amuse our family with a completely unrehearsed discussion between a Scotsman and an Englishman, complete with accents that had us in stitches. His repartee hopped back and forth between the two and that verbal jousting was as realistic as if two entirely different people were having the discussion. This is often a tool a writer equally gifted might use all by themselves. But another way to get this pep talk under way is to bounce it around with a couple other writers. Every mind works differently so looking at your cul de sac with a trusted group of writers can produce remarkable breakthroughs.

XX

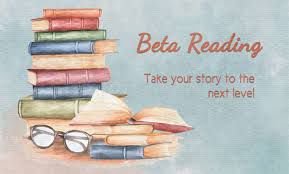

The other major way we see or find plot problems is to engage beta readers once our first drafts are complete. This is a fresh set of eyes, or two or three sets of fresh eyes, reading, not to find all the copy edits and misspellings, but to get a sense of how the story flows. If there are potholes, your beta readers will drive right into them and immediately realize there is a problem.

Sometimes it’s as simple as you knowing your character so well that you have her making choices and reacting to the events without actually considering why she is doing so. But the reader does not know the character as well as you do so they are suddenly left scratching their head wondering why. If they come back to you with a comment like, “I’ve no idea why Susan walked out like that.” Or “There’s just no way John would have done what you have him doing.” Clearly you’ve left some important information out, so you need to go back and add the emotions and thoughts of your characters that answer your beta readers’ questions. If your beta reader says that Jack had the patience of a saint in this confrontational scene, but his character up to that point wasn’t that of a patient person, you perhaps need to let the reader in on what was going through Jack’s head that kept him from reacting as the reader would have expected him to act.

Sometimes it’s as simple as you knowing your character so well that you have her making choices and reacting to the events without actually considering why she is doing so. But the reader does not know the character as well as you do so they are suddenly left scratching their head wondering why. If they come back to you with a comment like, “I’ve no idea why Susan walked out like that.” Or “There’s just no way John would have done what you have him doing.” Clearly you’ve left some important information out, so you need to go back and add the emotions and thoughts of your characters that answer your beta readers’ questions. If your beta reader says that Jack had the patience of a saint in this confrontational scene, but his character up to that point wasn’t that of a patient person, you perhaps need to let the reader in on what was going through Jack’s head that kept him from reacting as the reader would have expected him to act.

XX

Beta readers are not family and friends (although they can be if they approach the project objectively) Beta readers are not reading your book to give you glowing feedback and tell you it’s the best thing they’ve ever read etc. They are reading to tell you where they found problems: unexplained actions or reactions, unrealistic description, deviations from expected character behavior, outcomes that simply don’t make sense or resolutions that never happen. Sometimes, as I suggested before, overcoming these failures might just be a matter of information you skimped on, but other times it’s a huge black hole that needs to be illuminated, a pot hole in need of a road crew to fill it in or an entire plot line that needs reworking. Having good, honest

Beta readers are not family and friends (although they can be if they approach the project objectively) Beta readers are not reading your book to give you glowing feedback and tell you it’s the best thing they’ve ever read etc. They are reading to tell you where they found problems: unexplained actions or reactions, unrealistic description, deviations from expected character behavior, outcomes that simply don’t make sense or resolutions that never happen. Sometimes, as I suggested before, overcoming these failures might just be a matter of information you skimped on, but other times it’s a huge black hole that needs to be illuminated, a pot hole in need of a road crew to fill it in or an entire plot line that needs reworking. Having good, honest  beta readers can be an author’s best friend. If you are traditionally published it’s often your content editor who will point all these things out, but for both traditionally and independently published writers, having a reliable beta reader is your best hedge against plot failures. Beta readers along with brainstorming partners are your best resource for fixing botched plot lines.

beta readers can be an author’s best friend. If you are traditionally published it’s often your content editor who will point all these things out, but for both traditionally and independently published writers, having a reliable beta reader is your best hedge against plot failures. Beta readers along with brainstorming partners are your best resource for fixing botched plot lines.

XX

After all the fixing is done, send the book out again, perhaps to the same beta reader that gave you the feedback to see if they feel the problem has been fixed. You might also ask an entirely new beta reader who has not read this manuscript before. This is the best way to know if you’ve fixed all the problems, if your story makes sense and if the characters come across as real. Some authors I know also like to read their book out loud (to themselves.) That discipline of reading aloud can also reveal the places where there are problems.

XX

So, now that you’ve seen how an author who writes by the seat of her pants finds and fixes plot problems, check out some of these other authors and learn how Plotters fix problems (although I suspect most of them find their problems before they begin the writing process because they’ve already plotted the story out and likely they save themselves a lot of time and grief.)

So, now that you’ve seen how an author who writes by the seat of her pants finds and fixes plot problems, check out some of these other authors and learn how Plotters fix problems (although I suspect most of them find their problems before they begin the writing process because they’ve already plotted the story out and likely they save themselves a lot of time and grief.)

XX

Marci Baun

Connie Vines

Diane Bator

Beverley Bateman

Judith Copek

Dr. Bob Rich

Rhobin L Courtright